The first time I realized that my obscure knowledge of Rome had really sunk in was in the early to mid-aughts. Friends of mine had returned from a family wedding in the Italian capital. Specifically, the ceremony had been held at San Silvestro in Capite.

“That’s where they keep the reliquary of the head of John the Baptist!” I said, gleefully. I had most certainly been drinking but I was still impressed with my recall. My friends and I had a chuckle over my delight as we talked more about Rome and its macabre monuments.

Gruesome Aspects of History

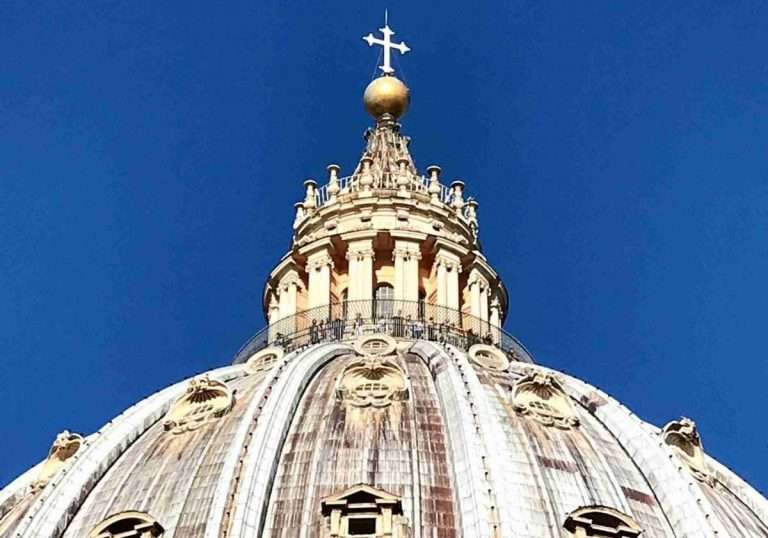

For as long as I’ve been attracted to Rome and Italy, I’ve been interested in some of the more gruesome aspects of its history: its slaughter of animals during Colosseum spectacles, the chapels that contain body parts and whole bodies of saints.

When you walk into Rome’s churches, you are literally walking on graves. And when you stroll through any part of this ancient city, you are stepping on top of sites where many people, from gladiators to Christians to non-believers, met their ends.

Images and reminders of death are everywhere here, which is probably one of the reasons Rome’s citizens have developed a coping mechanism — a zest for life — over the years.

These are heavy things to think about. But Rome’s past is especially fresh in my mind on those days when it is hard to turn on the television or open the paper (or browser tab) without learning about the latest horrible way that a human has died at the hands of another human or group of humans. There is no need for me to provide a link to any of these news stories; everyone knows what I’m talking about. But still it has been hard to square my interest in the minutiae of Rome’s destructive past with the horrors of today.

The Crucifixion of Saint Peter (1601)

The Beheading of Empress Faustina / Source

Just a visit to some of the well-known tourist stops in Rome remind me of current events.

San Silvestro in Capite has the head of John the Baptist in a silver filigreed reliquary. Santa Maria del Popolo has an exquisite and well-known Caravaggio that depicts Saint Peter being crucified upside down. Saint Agnese in Agone, the large church fronting Piazza Navona, has a side chapel with the head of Saint Agnes. She was 12 when a Roman prefect sent her to a brothel (for refusing to marry his son); she was eventually burned at the stake then beheaded.

In the upper church of San Clemente one finds the chapel of St. Catherine, which contains beautiful Masolino frescoes of the life of St. Catherine of Alexandria and the life of St. Ambrose. The beheading of Empress Faustina, who converted to Christianity thanks to Catherine, is depicted on the left side, a calm, colorful, 2-D rendering of a heinous act.

I could go on and on with the lovely art that depicts Christian martyrs and their horrible deaths: the crucifixions; the beheadings; the eventual saints that were drawn and quartered or buried alive or stoned to death. These gruesome stories add to the saints’ appeal. It shows the sacrifice they made for their faith. But the art still depicts the actual horrors that lead to martyrdom.

Of course, we don’t have as many works of art showing the torture that the Christians, once they came into power, inflicted on the non-Christians. But there are a few. The solemn statue of Giordano Bruno in the center of Campo de’ Fiori is a powerful reminder that there were men (and women and children) killed for putting forward ideas that were not in line with the church doctrine. Bruno was burned alive for suggesting that the universe is infinite, that stars are distant suns.

Giordano Bruno statue in Campo de’ Fiori in Rome

Memorial stones to deported Jews in Rome

Likewise, the Stolpersteiner (aka sampietrini), those tiny bronze pavements embedded in the ground outside homes of Rome’s Jewish citizens who were deported by the Nazis on October 16, 1943, memorialize those who were rounded up, tortured, and killed for being Other, for being powerless in the face of those whose power made them forget their own humanity.

How the Past Is Lost in Translation

I believe art and memorials are important. But the more that I see them around Rome — a city that has thousands of years of history painted on its church walls, engraved in its ancient buildings, and chiseled into statues — the more I am reminded of how torture and death are lost in translation from the stories we tell and the images we create of those stories.

Many of us are able to live with a sense of detachment from death. This is not to say that we have all had it easy and that we have not experienced the wrenching sadness of knowing death on a personal level. But death of the nature that is often depicted in famous art and enshrined in memorials around Italy has always felt like something that only happened long ago.

I still look at religious relics – the arms and doubting fingers and disembodied heads – with a sort of fascination. But while my thoughts used to be, “Look how barbaric humans once were,” I now think about how much further we — as a society, as humans — need to go.

A final note: as a quasi-agnostic, non-practicing, non-denominational Christian, I wish it were as simple as eliminating all religions. Humans get too exercised over beliefs that other humans have codified, no matter how absurd they may be. But I didn’t want to write this piece as an assault on religion. I’ve lived in majority Christian, Hindu, Buddhist, and Muslim countries and have known most people to be smart and kind and loving, in spite of or because of their religions.

Please read these other posts on “Lost in Translation” from the ladies of the Italy Blogging Roundtable. Note that we have a new lady, Michelle from Bleeding Espresso. Welcome!

Jessica – False Friends & A False Sense of Security

Gloria – Senza parole…

Rebecca – Lost in Translation

Alexandra – The alphabet of impossible Italian translations

Kate – Things my Sicilian Boyfriend and I fight about

Michelle – Lost in Translation: Adventures in Sola-tude

Post first published on February 20, 2015