At the entrance of the Foro Italico sporting complex is one of the most disturbing landmarks in all of Rome. Installed in 1932, the 17.5 meter-tall Carrara marble obelisk dedicated to Il Duce (Dux) Benito Mussolini is one of the few blatantly Fascist monuments to escape destruction in the years following World War II.

I say blatant because there are still remnants of the Fascist era all around Italy. The Fascist era lasted 21 years (1922-1943) and with it came many large-scale architectural projects and public works that are not so easily erased.

Memorials to the Italian Resistance

Monuments and memorials to the Italian resistance, to the partisans (i partigiani) who resisted both the authoritarian and racist Fascist state and the occupation of Italy by Nazi Germany (1943-45), can be found throughout the country. There are:

- Solitary wreaths hanging on buildings where slain members of the Italian resistance once lived.

- A cave on the outskirts of the city, site of a massacre.

- A museum.

- A grave.

- And so much more.

April 25, Liberation Day

The 25th of April is a national holiday in Italy called La Festa della Liberazione. April 25 marks the end of Nazi occupation in Italy during World War II and the beginning of the fall of fascism throughout the country. It is a day, at turns somber and celebratory, to reflect and commemorate freedom and Italian autonomy.

A day to observe Italy’s liberation was first written into law on April 22, 1946. It came nearly one year after partisans had declared an insurrection against Italy’s occupiers in advance of the arrival of Allied forces.

On April 25, 1945, Sandro Pertini, a member of the National Liberation Committee of Upper Italy (CLNAI), proclaimed a general strike (sciopero generale) against the Nazi-Fascist occupiers.

“Cittadini, lavoratori! Sciopero generale contro l’occupazione tedesca, contro la guerra fascista, per la salvezza delle nostre terre, delle nostre case, delle nostre officine. Come a Genova e Torino, ponete i tedeschi di fronte al dilemma: arrendersi o perire.”

Sandro Pertini – April 25, 2945 / Listen to the audio

“Citizens, workers! General strike against the German occupation, against the fascist war, for the salvation of our lands, our houses, our workshops. As in Genoa and Turin, put the Germans in front of the dilemma: surrender or perish.”

By the time Pertini announced the general strike from Milan, the headquarters of the CLNAI, many cities in northern Italy were yet to be free. Bologna (April 21) and Genoa (April 23) were the exceptions. Meanwhile, many cities in the south had already been liberated by Allied forces during their Italian campaign which had begun in Sicily in 1943. Allies liberated Rome on June 4, 1944, a success in the wake of devastating losses in the Battle of Montecassino.

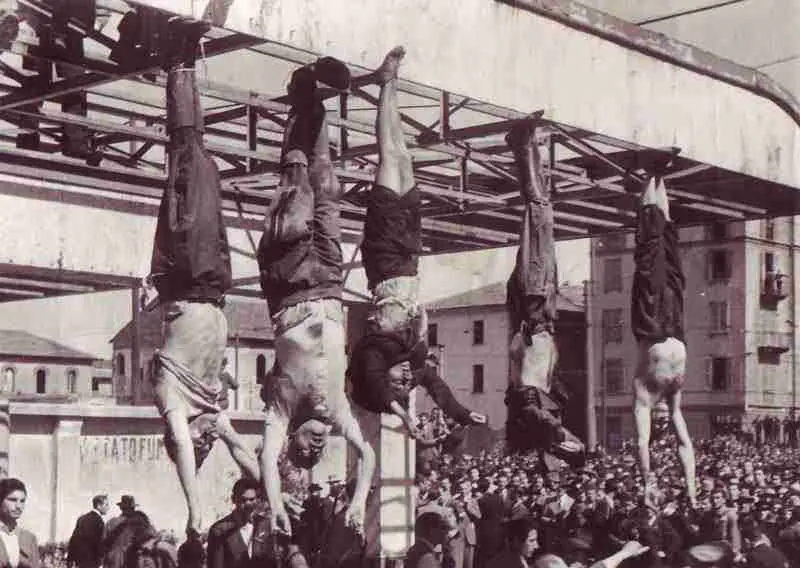

Following the CLNAI’s declaration of a general strike, it took less than one week for all of Italy to be liberated. On April 29, Mussolini, his mistress, and three of his men were captured, killed, and put on public display in Piazzale Loreto in Milan. All of Italy was liberated by May 1.

Per the New York Times regarding Mussolini’s death:

“The wretched end of Benito Mussolini marks a fitting end to a wretched life.”

Liberation Day, also known as the Anniversary of the Resistance, celebrates not only Italy’s liberation from Nazi-Fascism thanks to Allied troops but also the work of those who resisted in order to bring down the oppressive regime.

Liberation Day acknowledges the sacrifices of those who were persecuted by the Italian Fascists and/or by the Nazi occupiers. These include political prisoners, such as Antonio Gramsci, who was thrown in prison for 11 years because of his Communist views. It includes 335 Roman citizens — young and old, some partisans and some plucked from the street — who were executed in the Fosse Ardeatine in retribution for a partisan attack that killed 33 Nazi officers. Further, Italy’s Jewish community saw thousands of their family members sent to concentration camps during the time of Nazi occupation.

April 25 is also a day to remember that the ideals espoused by the resistance are constantly hanging in the balance. Recent years have seen the desecration of memorials to the Italian Resistance and threats to Italian Holocaust survivors. Victims of neo-Fascist terrorism, including 85 killed in 1980 during a bombing at the Bologna Centrale train station, are also honored on this day.

Indeed, the day is often steeped in partisan politics, of left versus right. But I would argue that April 25 is the most hallowed of public holidays, a day that Italians of all political stripes should embrace.

Without liberation, there would be no republic. And without Liberation Day, there would be no Republic Day. The latter, Italy’s national day, was determined by a referendum on June 2, 1946—41 days after Liberation Day became an official holiday.

Grim Reminders

Sadly, several sites associated with fascism live on. And they have increasingly become places of pilgrimage for both curious and ideological travelers.

For instance, Predappio, the small town in Emilia-Romagna where Mussolini was born and buried, has become a place of pilgrimage for those who inexplicably feel nostalgia for a dictator who sided with Hitler and the Nazis.

Rome is particularly rife with the symbols of Mussolini, from the Foro Italico in Roma Nord (still a right-leaning district) and the EUR neighborhood in Roma Sud. Buildings constructed for the Esposizone Universale Roma, the 1942 Expo that never took place, house the Museum of Roman Culture and the headquarters of fashion brand Fendi (Palazzo della Civiltà Italiana aka Colosseo Quadrato aka the Square Colosseum).

Should We Erase the Past?

Over the years a number of partisans and politicians have called for the removal of the Mussolini obelisk or, at the very least, the removal of the writing on the marble monolith. In 2015, prior to the 70th anniversary of the end of WWII, members of parliament debated this very question, with most members — even left-leaning ones — against the removal.

“We are an anti-fascist country,” said Matteo Orfini, president of the PD. “The principles of the anti-fascist struggle are written in our Constitution. We do not need to erase our memory, albeit at times dramatic.”

MP Stefano Pedica added: “Eliminating the word ‘dux’ from the obelisk of the Foro Italico is a meaningless proposal. To eliminate the history of fascism…will we ask also to have the whole EUR district razed to the ground?”

Conclusion

Mussolini was obsessed with restoring Rome to its former glory as an empire. Therefore, he of all people should have been familiar with what happened when one regime fell to another. For example, Nero’s Golden Palace was demolished to make way for the Flavian Amphitheater, aka the Colosseum.

To the victor go the spoils. Italy is an antifascist republic by law, not by opinion.

I am not impressed by Italian government’s all-or-nothing, shrugged shoulders approach to eliminating leftovers from the losing fascist side. EUR can remain — it was not completed during Mussolini’s reign.

But the Mussolini obelisk has to go. It is an eyesore, an embarrassment, and an insult to the memory to those who suffered under Nazi-Fascism.

Scholars have been claiming for years that Mussolini left a message under the marble structure, understanding that it would never be read until the obelisk was toppled and his empire at an end. Why not remove the obelisk to find this note from the past? The marble can be recommissioned for use in art projects or to create gleaming white jersey barriers to protect the exteriors of resistance museums from bombs.

I know that last part sounds harsh. But I am seriously concerned for the world right now.

Liberation Day, April 25, is more than just a day off in Italy. It is a lifeline to the past that we are quickly forgetting.

Learn More

- ANPI – Associazione Nazionale Partigiani Italia

- ANPI List of Resistance Memorials in Italy

- The Italian Campaign – Overview from History.com

- Liberation Routes Italy

- April 25: The Day of Liberation – Web Doc from RAI Cultura

- April 25, 1945: Photos of the Liberation

Post first published on April 25, 2020