Italy has long been at the forefront of writing and the written word. From scrolls to printing presses and filaments to fonts, writing history has been made and has flourished in Italy over millennia.

As a writer and lover of all things Italy, I eat up these little tidbits of written history—when I can find them. Museums in Italy are often so packed (and blessed!) with art and historical fragments that artifacts associated with the written word are shoved off to side galleries and tucked into hidden libraries, left to gather dust in the shadows.

Here are just a few of the items and exhibits that have delighted the writer in me.

Ancient Writing and Texts

So many words that were written during ancient times are available to even the casual visitor to Rome. Marble blocks are chiseled with Latin phrases and abbreviations on ruins the Roman Forum and on artifacts housed in museums across the country.

But how did these ancient people write and with what?

The Museum of Written Communication in the Roman World, Rome

One place to look is The Museum of Written Communication in the Roman World, a gallery and dispersed exhibit within the Baths of Diocletian branch of the National Roman Museum.

The epigraphic collection contains around 900 items, including texts “written by people belonging to all social strata, from emperor to slave, and bear witness to the daily lives of men and women living many centuries ago.” You’ll find funerary monuments, seals, and altars with inscriptions dating from the 7th to the 2nd centuries BC.

The Baths of Diocletian also has a replica of the Fibula Prenestina, a golden brooch said to contain the oldest inscription of old Latin, dating from the 7th century BC. Archeologists have debated its authenticity for more than a century. The original fibula is housed in the National Museum of Prehistory and Ethnography “Luigi Pigorini” in Rome’s EUR District.

National Etruscan Museum, Rome

Across town, the National Etruscan Museum houses yet another example of ancient writing. Here you will find the 6th-century BC Pyrgi Tablets. These three, perfectly preserved, gold tablets are engraved in Etruscan and Phoenician.

Iguvine Tablets, Gubbio

Beyond Rome, there are several other places to find artifacts engraved with ancient languages. One such town is the Umbrian hill town of Gubbio, which prides itself on its Iguvine Tables. These engraved bronzes, dating from the 3rd- to the 1st-century BC, are inscribed in the ancient Umbrii language and housed in Gubbio’s Palazzo dei Consoli. They are also known as the Eugubine or Eugubium Tablets (Tavole Eugubine, in Italian).

First Examples of the Italian Language

Florence announced in 2020 that the city would be the future home of the National Museum of the Italian Language. The announcement was made to coincide with the commemorations marking the 700th anniversary year of the death of Dante.

National Museum of the Italian Language, Florence

When it opens, the National Museum of the Italian Language will have on display early editions of Dante’s Divina Commedia as well as the Placito di Capua, a document dating from 960 that is the first known document written in the vulgate. Until then, you can find a copy of the Placito di Capua on exhibit in the Museum of the Abbey of Montecassino.

Though Dante is considered the Father of the Italian language, the Placito di Capua attests to the fact that the vernacular was in wide use long before the poet took quill to paper in the 13th century.

Basilica di San Clemente, Rome

Another, more amusing example of the first use of vernacular is in the Basilica of San Clemente in Rome.

The Inscription of San Clemente and Sisinnio dates to around the end of the 11th century and is considered the first example of the Italian vernacular used with artistic intent.

Part of a fresco, the inscription details an interaction between San Clemente and the nobleman Sisinnio and his servants. Sissinio had ordered that Saint Clement be dragged to prison because Sissinio was angry that his wife, who had recently converted to Christianity, had been influenced by Clemente. But Clemente has miraculously freed himself and the servants find themselves dragging a heavy column instead.

Saint Clement’s words are expressed in Latin (the proper language) while Sisinnio and his men speak in the vulgate.

SISINIUM: “Fili de le pute, traite!”

GOSMARIUS: “Albertel, trai!”

ALBERTELLUS: “Falite dereto co lo palo, Carvoncelle!”

SANCTUS CLEMENS: “Duritiam cordis vestris, saxa traere meruistis.”

The translation reads:

- SISINNIO: “Sons of bitches, pull!”

- GOSMARIO: “Albertello, pull!”.

- ALBERTELLO: “Get behind him with the pole, Carvoncelle!”.

- SAN CLEMENTE: “Because of the hardness of your heart, you deserve to drag stones.”

This example of vulgar Italian is actually closer to today’s Romanesco dialect of Rome—especially the “file de le pute” part.

First Fonts

With the advent of Johannes Gutenberg’s printing press in 1440, there was a need to standardize type. Renaissance Italy—home to multiple universities, the papacy, and aristocratic courts—was especially eager for the printed word and tools to speed up its production.

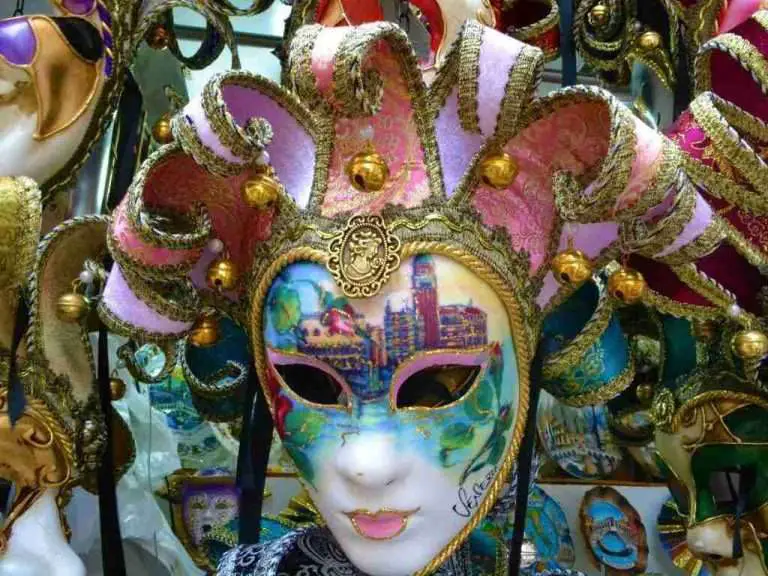

Early Printers and Typefaces in Venice and the Veneto

In his book Just My Type: A Book About Fonts, Simon Garfield explains that Venice, a leader of innovation in the 15th century, was also at the forefront of the printing press industry.

With matrices, moulds, and type, there was suddenly a new commodity on the market, and the center of trade and the heart of printing was Venice.

In Venice, more than 50 printers competed for the passing merchant’s attention, and clarity was a strong selling point. The da Spira brothers from Germany established their Venetian type in the city in the 1460s…it is easily readable to us today, the eye gliding rather than snagging along it, the first truly modern printed font.”

Just My Type: A Book About Fonts by Simon Garfield

Venice’s Marciana National Library, located on Piazzetta San Marco, contains a trove of printed treasures, including the first book ever printed in Venice by Giovanni da Spiro (née Johannes Von Speyer). It was Epistolae ad familiares by Cicero.

Garfield also discusses the Venice-based French typographer Nicolas Jenson, who is known for creating the first Roman-style font; Aldo Manuzio, innovator of moveable type that looked like handwritten script and of the “pocket book”; and Venetian goldsmith Francesco Griffo, who first introduced italic type.

About Griffo, Garfield writes:

Many of the types for [the ancient texts that illuminated the Italian high Renaissance] were in fact cut by the goldsmith Francesco Griffo. It was Griffo who created the ancestor of the classic Bembo font—which he devised to set a brief account of a trip to Mount Etna by a Venetian cardinal—and, around 1500, introduced italic type—not as a method of highlighting text but of setting entire books in a more condensed form.

Just My Type: A Book About Fonts by Simon Garfield

Two more places to explore the history of the written word in the Veneto region are Verona and Treviso.

In Verona, the municipal libraries have thousands of rare manuscripts, including originals from da Spiro, Manuzio, and Jenson. Meanwhile, Treviso is home to the hip Tipoteca Printing and Type Design Museum, which has a collection of manuscripts, antique printing presses, and an extensive archive of metal and wooden type blocks.

Museo Bodoniano, Parma

Fast forward a few centuries and move west about 162 miles (261km) and you will reach Parma, another important center for fonts and the printed word.

Parma’s Museo Bodoniano, Italy’s oldest printing museum, is dedicated to Giambattista Bodoni, creator of the “Bodoni” font.

Giambattista Bodoni of Parma and the Parisian Firmin Didot are the designers credited with inventing the “Modern” class of typefaces in the 18th century. These faces appeared in the 1790s, when improved printing techniques and paper quality enabled the punchcutter to cut far thinner strokes without a risk of cracking or disappearing on the page.

Just My Type: A Book About Fonts by Simon Garfield

The Bodonian Museum is laid out in three sections, which are dedicated to print before and after Bodoni, the Italian craft of bookbinding, and the personal and professional history of Giambattista Bodoni. In the collection are rare documents, letters, and manuscripts printed in Bodoni; printing tools, including seals, stamps, punches, and letter casts; and a reproduction of Bodoni’s printing press. It also has a library devoted to books about printing, type-setting, and the history of fonts.